My father [Leopold Barth] dealed with cows.

He goes to the market.

The farmers bring their cows that don’t give milk anymore. Farmers want milk from their cows. They brought them to the market.

There were cow markets, horse markets, sheep markets, all kinds of animal markets.

My father bought cows from the farmers.

Other farmers who lived nearby came every Sunday to see what cows we have, and bought cows.

My father bought trainload full of cows.

Now we have trains to transport packages and such stuff. These were trains to transport livestock…

Some gave milk and some don’t.

The ones that don’t give milk, the butcher came and slaughtered them … and after the slaughterhouse, the butcher went and brought the meat home and cut it in pieces – calf meat or beef meat, whatever it is …

Trainloads full.

Some days the farmers nearby brought cows that gave milk … that they used for their acres to plow. They have a tool that they put the cows before [a plough] and they make grooves that they put the seed in or potatoes.

That was a big business!

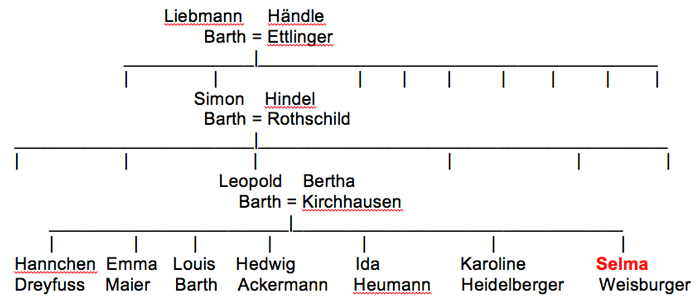

{Selma}

By 1827, the Jews made up 14% of the population of Flehingen.

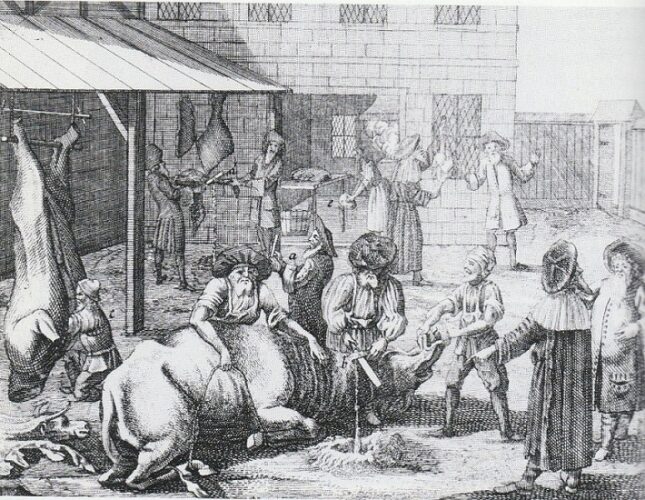

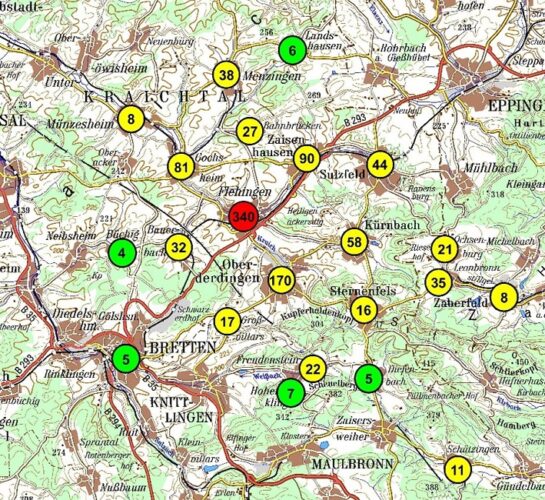

Flehingen was also the center of the cattle trade in the rural Kraich District between the towns of Bretten, Eppingen, and Bruchsal.

Verkäufer = sales Käufer = purchases pink = Jews green = Christians

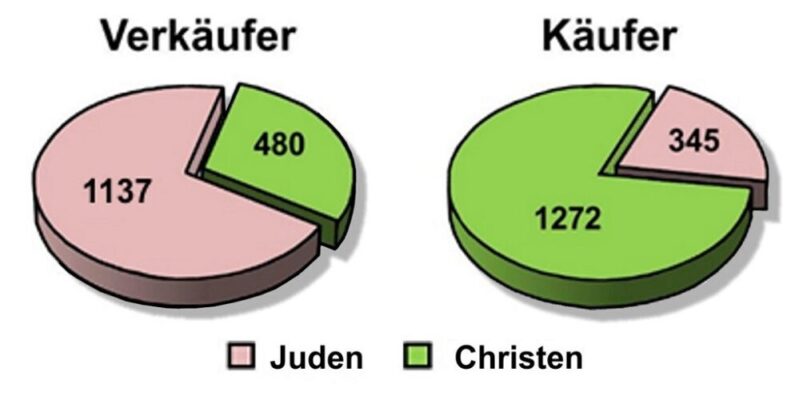

Many of my relatives in Flehingen were cattle or horse dealers.

My great great great grandfather – Lippmann or Liebmann Barth – born around 1781, was a cattle dealer.

His son, Simon – my great great grandfather – was a cattle dealer.

Simon’s sons, Leopold – my great grandfather – Lazarus, Lippmann, and Moses were cattle dealers.

Leopold’s only son, Louis, who was killed in World War I, was a cattle dealer.

Of Leopold’s six daughters, three married cattle dealers – Berthold Ackermann (whose father Jakob was also a cattle dealer), Samuel Heidelberger (many Heidelbergers were cattle dealers in Flehingen), and Max Heumann.

One daughter married a horse dealer – Siegmund Maier.

One married the owner of a butcher shop and sausage factory – Ludwig Dreyfuss.

Only my grandmother married out of the business entirely – Willy’s father Louis Weissburger ran a hardware store in Kochendorf. Willy used those skills to develop a business wholesaling appliances in Stuttgart.

Cattle dealing involved many skills that were passed down from generation to generation.

How much does that ox weigh? “Dad [Berthold Ackermann] had the uncanny ability to guess the weight of a cow or steer within a few pounds.” {Erna}

Do we have the capital saved up to make that purchase?

How long will it take to find a buyer? How far will we have to go to find a buyer? How much feed will we have to pay for in the meanwhile?

How many head will we have for the monthly market in Bretten and does it make sense to rent a prominent stall or not?

If the payment terms were delayed, for how long and would there be interest charged or not?

If one animal was bartered for another or if part or all of the payment was to be made in goods (grain or armchairs) or services (plowing or weaving), how was equality in value determined?

Cattle leases were especially complicated and often left the farmer feeling cheated.

In them, the dealer would give a cow to the farmer.

The farmer would pay for feed, could use the milk and dung, and could use the cow to plow his fields.

After the two-year lease period, the farmer would have the option to buy the cow or make a lease payment.

If the cow had two calves in the two years (zu Dreyen dasteht in Yiddish), the farmer could return the cow and keep one of the calves for himself.

Deals that included the charging of interest also gave rise to resentment among the farmers.

The charging of any interest at all was called usury, was considered a sin if done by Christians, and was one of the dirty jobs Jews were allowed to do.

Many Jews bent over backward, offering lenient payment terms or not charging interest.

He [Louis Barth] was a cattle dealer.

When he came to a village, the first step was city hall.

Who is sick? Who needs?

He left there.

Then he would send, if they needed, food or medicine or money.

And then he would start business.

In every village he entered.

Very religious, he did a lot of good.

{Erna}

Christian farmers were their trading partners and they couldn’t afford getting a bad reputation.

Nonetheless, Christian farmers were quick to scapegoat the Jewish dealers, blaming them for all their money troubles, many of which had nothing to do with Jews.

For example,

“In Baden in 1833 the abolishment of the feudal tithe [emancipation of the serfs]… was associated with a transfer fee that amounted to up to twenty times the average annual income of Baden farmers, though one-fifth was subsidized by the state treasury.

This was one of the main causes of decades of debt.” {Bölcke quoted in Schönfeld}

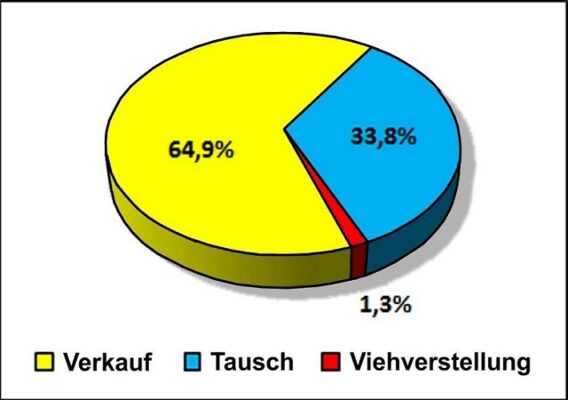

In a study of all cattle deals done in Flehingen between 1850 and 1858,

“Interest claims that could have justified the charge of usury are not recorded in a single record,” and only 1.3% were cattle leases. {Schönfeld}

yellow = sales blue = barters red = leases

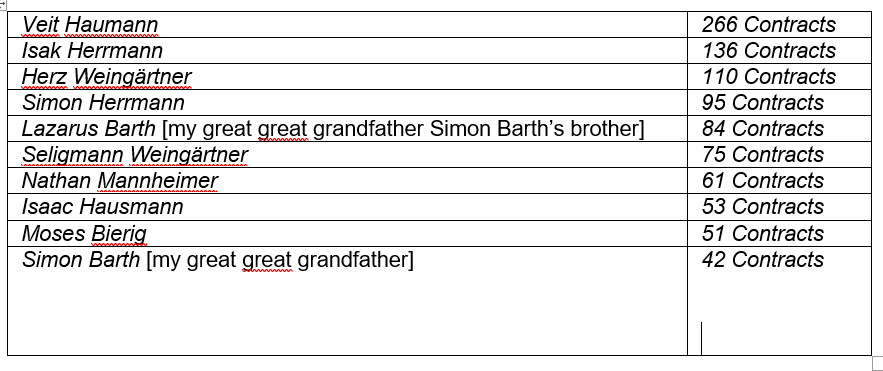

In 1933, the nazis prohibited any new cattle dealers “of Jewish descent”.

Samuel Heidelberger – Selma’s sister Karoline’s husband – died in 1936.

Their eldest son Siegbert wanted to take over the business, but was denied permission because he was a Jew.

At the time, there were eight Jewish cattle dealers operating in Flehingen and one Christian “who probably lacks the necessary working capital to really trade properly.” {Mayor Becker’s evaluation of Samuel’s application as quoted in Schönfeld}

By 1938, the number of cattle markets in Bretten had been cut in half.

By the end of the 1930’s, “sales fell so far that cessation of the cattle market was considered.” {Straub as quoted in Schönfeld}

The nazi’s obsession with eliminating Jews no doubt contributed to food shortages among Germans when WWII broke out.

5,355 total views, 3 views today